By Eva Zhu —

Sarah Law rarely shops alone anymore.

She doesn’t want to be the next victim of an anti-Asian racist attack fueled by COVID-19.

For a few weeks in May, the 20-year old didn’t leave her house at all, she says. As a Chinese Canadian living in the majority-white community of Steveston Village, B.C., Law was afraid just being out in public could draw racist attention.

Warning: This story contains racist terms that may be hurtful

Reports that two men had verbally attacked and then tried to run down two Asian women with a car that month added to her fears.

“(I stayed) home so no one could have the opportunity to yell at me, or spit on me, or kick me or (do) anything else that was happening on the news,” she says.

These days, if Law needs groceries, she tries to bring a friend. When she had to go alone recently, she wore specific clothes as a precaution.

“(I) dressed in head-to-toe Oak + Fort and Aritzia, to look as white-washed as possible,” Law says.

Anti-Asian xenophobia

Law’s fear of being a target comes as media outlets report a surge in assaults on Asian people, young and old, after the World Health Organization said the novel coronavirus originated in China before spreading around the world.

Since then, some people have used the origin of the virus as fuel to justify and excuse racist anti-Asian sentiments and actions.

Some of the incidents have been alarmingly brazen. Canadian singer Bryan Adams posted a racist Instagram video accusing “bat-eating, wet market animal-selling, virus-making greedy bastards” of causing the coronavirus in May. He later apologized.

In May, Vancouver Police announced a spike in anti-Asian hate crimes and hate related incidents, saying the department had opened 29 investigations this year compared to four in 2019.

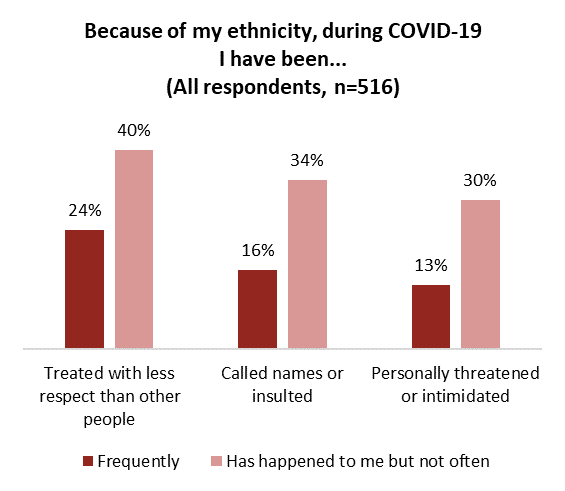

And an Angus Reid Institute-University of Alberta poll surveyed more than 500 Chinese-Canadians and found “50 per cent reported being called names or insulted as a direct result of the COVID-19 outbreak and 43 per cent further say they’ve been threatened or intimidated.”

Like Law, 61 per cent of the survey respondents said they had adjusted their daily routines to avoid possible racist encounters.

One Canadian researcher who studies race and racism said in crisis situations such as a pandemic, racism that is already present in society rises to the surface. People who have been covert may begin to feel emboldened, said Pamela Sugiman, dean of Ryerson’s Faculty of Arts, in an article published on the university’s website.

Sugiman said racism became legitimized for some people in March, when U.S. President Donald Trump called the coronavirus the “Chinese virus” at a news conference.

In April, Trump pushed a theory that the coronavirus originated from a laboratory in Wuhan, and during his June 21 rally in Tulsa, he called COVID-19 ‘kung flu.’

On-campus racism

The increase in overt acts of racism against Asian Canadians has since bled into all facets of society, including post-secondary institutions. A June 22 report released by Western University about on-campus racism mentioned instances where Asian international students felt stigmatized by hurtful comments related to the coronavirus.

They were also targeted for wearing masks and coughing in public, the report says.

McMaster University graduate Diana Chu says she could sense people avoiding her when they noticed her wearing a mask early on during the pandemic, she says.

“When I was out with a mask on, like on the bus or the grocery store, people would make an effort to distance from me in a way that was definitely more than necessary,” Chu says.

Around that same time, a Chinese-Canadian University of Ottawa student, Yanni, says she went out to buy masks, just to be prepared.

But when she asked a sales associate at the store to help her locate the masks, he took off, says Yanni, who didn’t want her last name used in this story.

“When I was in Walmart, that salesman just ran away when I asked him ‘Where’s the masks?'” she says. “He literally ran away.”

Yanni says many of her Asian friends have experienced negative interactions that seem to be racially motivated since the pandemic hit.

“Some people even yell at them on the street.”

A CBC article about a Western student who was infected with COVID-19 said her return to campus filled people with dread. Peers only calmed down after doctors praised the student for “going above and beyond to protect the public by wearing a mask and isolating herself,” two acts that were not common in Canada six months ago, said the article.

Not a new phenomenon

While the COVID-19 pandemic has put anti-Asian sentiments and acts into the headlines, they’re old news to many in the Asian community.

Last year, when Law received an unusually low paper grade in a sociology class at Simon Fraser University, she says the first thing her professor gave her wasn’t an explanation, but a question about how many languages she spoke.

First her professor asked whether she spoke any languages other than English at home. Then the prof said people who do speak multiple languages often “can’t write well because it can be challenging for the brain,” she says.

Before agreeing to take a second look at the paper, the professor told Law she would have to email her transcript and past papers as evidence that she could write well.

“I had to go all the way back to high school to prove I was put in advanced placement English literature in Grade 11 for them to agree to re-mark my paper,” she says.

Law says she also frequently experiences “microaggressions” — which are described as racial insults and demeaning comments based on race that can be subtle and even unintentional — on campus.

As a result, she’s careful to never give someone a reason to use her racial identity against her, even though that responsibility shouldn’t be on her shoulders.

“The ramifications for me if I do have an outburst and truly fight back are so high that I just get stuck in this constant battle of ‘make sure people listen to you when you speak,’ and ‘why should I have to work twice as hard to find a way to be listened to when they never intended to listen to me in the first place?’”

Although there’s no simple solution to stopping these racist attacks on Asian people, non-profit research institutes (Angus Reid Institute), grassroots groups (Project 1907) and Asian lead organizations (Stop AAPI Hate) across Canada and the United States have been keeping detailed lists and collecting data on anti-Asian crimes.

‘I was just a kid’

Chu’s first recollection of racism occurred on her 12th birthday.

It was at Vancouver’s Pacific National Exhibition.

“I bumped shoulders with a white older man when I was walking. (I) apologized, and he responded by calling me a ‘chink.’”

Her best friend laughed. Chu said she also tried to laugh it off, but the slur hurt.

“I definitely felt the hurt of those words when I was on my own,” she says.

“It was the first time I had been called a racial slur and I was just a kid.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.