By Mira Williamson —

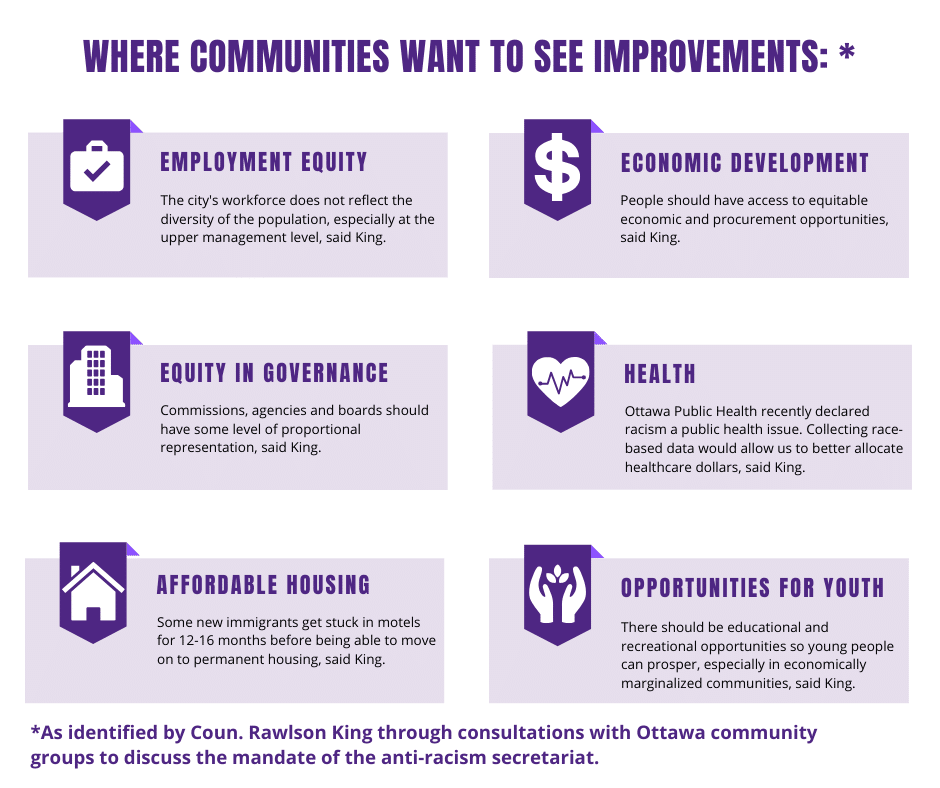

The City of Ottawa has hired an anti-racism and ethnocultural liaison to lead its new anti-racism department. This newly formed department will help the nation’s capital look at all municipal policies—from active transportation, to roads, to public health through an equity lens, said the liaison, Coun. Rawlson King.

King, who is also Ottawa’s first Black councillor, spoke with Western Journalism Studio’s Mira Williamson about his role and how it will impact change on many levels.

Read excerpts of their conversation below (interview has been edited for length):

Q: First, congratulations on your new position and for securing funding for the anti-racism secretariat. What is the plan moving forward?

A: Having a wider conversation. As a city councillor, I could only have a narrow one, but they can have a better city-wide consultation and conversation with multiple groups. Also [it will] ensure that there’s education about racism in the city and how that affects different groups. And then, the last focus of the policy unit of course, would be policy prescriptions—ensuring that the problems that are identified, that can be addressed and are within the jurisdiction of the city to address, are looked at, and that there are policies that emanate from that, that are approved and ensure that we measure and monitor the existing policies that we have in place. Because unless we measure what we’re doing, we can’t tell its effectiveness. So it’s obviously a large mandate, but that’s the idea: it’s really to redress institutional challenges that people are having when they’re dealing with their city government.

Q: I’ve read that some groups are concerned that as the first and only Black councillor in Ottawa, heading up this anti-racism secretariat could place undue expectations on you. What are your thoughts?

A: Well, I don’t know, I ran for office to make change. It’s just time for action. I’m the person around the table, and representation matters, and there’s an opportunity for change. Change really will just emerge from people who have an understanding of the impacts, the negative impacts, of inequality on communities. And the other thing is that this should also be a joint task. It’s not just me. There are community members who are working hard every day, working to fix things. But, you know, if in a different scenario, even if I was around the table, would it really make any sense to appoint somebody else as liaison when you look at who’s around the table? Probably not. So I just look at it as a challenge. It’s part of the challenge of, and part of the responsibility of being elected is to move forward with positive change.

Q: And I know that you’ve been talking a lot with community organizations and members.

A: There’s thousands of people who’ve been actively advocating for change, and they make as massive an impact as a policy maker. But somebody who’s a decision maker around the table—they’re ineffective if they don’t make decisions. And there’s somebody around the table now who’s saying these are very important priorities. And they’re important because, you know, we’re talking about basic human rights and equity and social cohesion. It’s going to be a lot of work, but my feeling is that we have a tremendous number of people in the community who work every day at making the community better. So, I never really kind of take it from that negative viewpoint that, ‘Oh, I’m the only person; everything is on my shoulders.’ I feel that, but I don’t complain about it. I mean, that’s just the role.

Q: I saw that one of the goals of the secretariat is to apply an anti-racism lens to all the policies that are being developed. Can you speak a little on how changes to transportation, for example, might be examined under an anti-racism lens?

A: If we’re thinking about active transportation, the extension of cycling lanes and cycling infrastructure is important for low income people. So, I represent a neighborhood, Overbrook, that has high needs, and it has a higher proportion of people who actually will walk or cycle to work because they can’t afford a vehicle. So this type of infrastructure does benefit people. And that’s the thinking—we’re not just creating this infrastructure or maintaining this infrastructure, just with the traditional view of moving traffic efficiently around the city during rush hour. We’re also kind of ensuring that we encapsulate and incorporate the people who would actually be utilizing these roads or this infrastructure. It’s the same thing, you know, maybe lower income families have vehicles that they depend on to get to their jobs. Should we be thinking about prioritizing road renewal and road maintenance cycles? Ensuring that maybe the roads in lower income neighborhoods don’t have as many potholes, especially when you think about the prohibitive cost to fix somebody’s vehicle if their household income is under $45,000 – $30,000 a year. Well, these are the things that we have to kind of superimpose and start to think about.

And that’s what I think an anti-racism lens is like. Same thing in health. We’ve seen that with COVID-19. We know that the respiratory illness has a disproportionately negative effect on our Black communities and other racialized communities. So it’s important for us to collect the data, to determine what the best approaches towards improving health outcomes are. So that’s the idea; it’s kind of at least giving some conscious thought to the impacts on different groups in the city and ensuring that we can have a quality of outcomes, equity of outcomes and improved outcomes, by thinking about how we apply those resources in that context.

Q: Tuesday you had an event to talk about the secretariat with kids. How did that talk go?

A: I think it went well because we were really just talking about differentiating things and what the city does and why it’s important for us to build a city together. Kids are very bright, and some of them worked at defying the fact that they have Black friends and they know that their black friends are treated differently or bullied. And so what we wanted to do was talk about the commonalities. That we’re more in common than different, that those kids, the parents of the other kids, the Black kids, want the same benefits. They want their kids to grow up in a safe environment, get a good education, have a good job, be able to raise a family. They have all the same wants and desires. And the challenge of course is that when they deal with governments or deal with other institutions, they’re not treated equally, and you should be before the law—everybody should be treated equally by their government…

But the reality is that when people don’t see themselves as being equal and do not see any capacity to go to their government, go to their city, go to Parliament Hill and actually make meaningful change, that results in breakdown…I think in Canada people still have a view that we can strengthen our cities, build them up. So that’s why it’s important to a lot of people in the city. I was telling the kids, the idea of a unit at the city that helps do that.

Q: Lastly, I have a question about journalism, because I know that you have degrees in both journalism and communications. A lot of journalists of colour are speaking out about racism in newsrooms and racist coverage. My newsroom is all student journalists. I was wondering if you had any thoughts on how we could do better when we graduate and enter these newsrooms.

A: I saw people rightly pointing out challenges with anti-racism, anti-Black racism and issues at Carleton [University], and saying that the classrooms should be more representative of society, which I agree with. Of course, the challenge for the schools is that the newsrooms aren’t representative yet of the population. And so we have to get there. So I think that the most important thing is ensuring that when people leave school, they actually do go to the newsrooms—because I never seriously considered the newsroom…

I think that at this point, you need corporate management to really demonstrate in the newsrooms that they’re committed to true diversity and not just tokenism…It’s more you just want the best opinion writer of a diverse background writing about everything and contributing in a fulsome way, and commenting in a fulsome way about Canadian society, or the economy, or business, sports. I think that there has to be a different view to say, you know, we have a diverse, multicultural society—that should be reflected in the newsroom. And once that starts to be reflected in a substantial way in the newsroom—it will take time—then we’ll see retiring journalists who go on to academe and start being instructors…I mean, we’re seeing a lag and we see a lag in the newsroom, and people are rightly pointing that out…It’s a catch 22, if there are not enough people in the newsrooms, then you’re not going to see a lot of instructors in the schools, despite the fact that the faculty could be well-meaning and say ‘We want diversity,’ but you know, the question is where are the candidates? My suggestion is if you want to make an impact on the field at the end of the day, and at some point teach after a 10 or 20 year career in a newsroom, you’ve got to be able to fight and make sure that you can survive and thrive in that newsroom to get to that other point of teaching.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.