By Vicky Qiao ––

First launched in 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement has attracted skyrocketing levels of participation and intensity since the May 25, 2020 killing of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by the Minneapolis police.

While mass rallies to protest anti-Black racism are happening around the world, the movement has also been gaining new engagement from diverse groups — including non-Black, people of colour (POC) communities.

For the past month, Diyana Noory has been among the activists in those communities participating in #BlackLivesMatter on social media, compiling resources, amplifying Black voices and urging other POCs to recognize the privilege and compliance within their own communities.

A daughter of Iraqi immigrants who grew up in London, Ont., Noory is the founder of the Middle Eastern/North African Law Students Association. She said she was in high school when she first started to understand the ideas surrounding anti-racism and white supremacy.

“Before high school and [in] elementary school, I guess that was the point of my life where I was trying to assimilate (into the white majority),” she said. “I think over time I just understood it wasn’t going to work. And I understood that at an early age, I was always going to be different.”

She also came to realize that trying to assimilate into mainstream, white culture can also create a tendency to ignore deeper problems of racism and discrimination or adopt ideologies that perpetuate racial stereotypes and harmful ideologies.

“The undercurrent of it all is white supremacy… within our particular groups, people who perpetuate anti-blackness are trying to align themselves more with white supremacy and gain that privilege,” she said.

Aside from her advocacy on social media, Noory has also been having conversations with her family and relatives.

Many first-generation immigrants have overcome challenges and barriers to establish a new life for their family in Canada or the United States, Noory said. As a result, some may be reluctant to challenge the established status quo and power structure.

“We have a duty to stop (anti-Black racism) within our own circles,” Noory said, “That’s one of my main motivations… I have to keep, keep, keep pushing, because if I don’t, there’s no one else.”

In North America, Asian immigrants have long been associated with the “model minority” identity— especially the East Asian community. “Model minority” is a term used to label certain racial minority groups based on the notion that they are studious, hard-work, law-abiding people and act as role models for other ethnic communities.

For many Asian activists, this perceived superior social status can act as a major roadblock to confronting white supremacy and systemic racism—especially when internalized by the community itself, said Angela Sun, a theatre artist based in Toronto..

“I think for a lot of Asian immigrants, or even people who’ve been here like one or two generations, it’s like if you keep your head down, if you stay quiet, if you just work hard, things will work out for you,” she said.

Sun said the immigrant experience can lead to the illusion of equal opportunity and the so-called “American Dream.”

Like Noory, Sun said people need to understand the danger of internalizing the model minority identity. For the East Asian community, in particular, she said anti-Chinese sentiments and racism that surfaced during the COVID-19 pandemic shows the fragility of the model minority identity. .

“If you’re physically a part of the Asian diaspora, you will be perpetually a foreigner to white supremacy,” Sun said.

“And the only reason why white supremacy decides to position one group as the ideal minority, as a model minority is to keep other communities down, especially Black communities. But we are all within this overarching racist system.”

Sun recalled being part of the Black Lives Matter movement and protesting the killing of Andrew Loku by Toronto police in 2015, where she was exposed to and astounded by the overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous peoples in Canada’s prison system.

She said the reality of police brutality and systemic racism urged her to start educating herself and increasing her own awareness.

“It’s been the people who’ve been affected by something like this, who have largely carried the burden for making people aware,” Sun said. “That’s just ridiculous to me that families aren’t able to mourn or receive justice. And instead, they have to give this additional labour to make anybody care.”

When it comes to raising awareness and resisting anti-black ideologies within the Asian community, Sun said it’s important to start with oneself and those around you.

“I think there’s also incredible power in just examining yourself and thinking about these issues and how you yourself might have contributed even in the smallest way, and think about how maybe next time [when] these situations happen, you notice them and you change them.”

Atlanta-based spoken word and hip hop artist Sun Park has been one of the leading organizers of the annual Asian Allies Convo and has been an administrator for the Asians4Black Lives Facebook group.

Park said anti-black racism has a global ripple effect, which has manifested within her own family. “My personal history with this is that I was disowned by my father in 2010 for dating a black person. He is Korean and I’m of South Korean descent.”

“And so a man, my father, who has never lived outside of Korea except for a short [time] has internalized black anti-Black racism in a land where Black slavery was never a thing.” she said.

. When discussing anti-Black racism within the Asian communities, PArk said it can be frustrating when the conversation often turns back to the oppression and disadvantages faced by themselves.

“I think it’s such an interesting thing for us, especially as a non-Black POC, to look at how we are both simultaneously victims and benefactors of the system of white supremacy depending on the context that we’re in,” Park said.

“We either can be at the front end of the stick of receiving racism, or we could be in the seat of position of privilege to perpetuate oppression.”

Park said since her team established the Asian Allies Convo In 2016, many participants have become organizers over the years. “The folks who are at the table currently for Asians Allies convo, which is now across Canada and the U.S., that’s a brand new batch of people that came together over the course of the last eight months or so.”

The organizers also started the initiative of Letters for Black Lives—first started by Asian American organizers and then adopted by those in Canada.

The Canadian version of the open letter includes more than 18 translations contributed by hundreds of volunteers. The goal is to provide tools for people to have conversations with families and communities on anti-black racism.

With #BlackLivesMatter gaining support across racial groups and the internet, ‘ally’ has first become both a wide-used term and a highly debated concept.

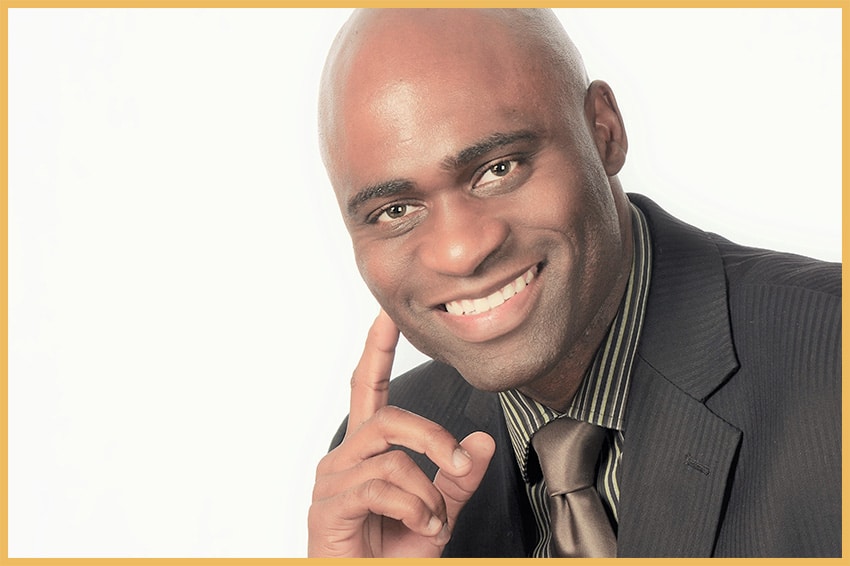

Leroy Hibbert, the Multicultural Outreach Program Coordinator at LUSO Community Services in London, said true allyship means listening and supporting.

“One thing you have to be aware of is not necessarily speaking for the community but standing with the community, and asking the community what [you] can do to support the community that [you] are standing with,” he said. “Which basically means pausing to hear what they have to say.”

The conversation won’t always be easy, and certainly won’t be easier within the POC communities. But activists like Noory said they have the responsibility to urge the community members to recognize their own complicity in white supremacy and break apart from it.

“As racial minority groups, we all have benefited from Black activism, whether that be with immigration or property rights,” she said.

“We can have an action plan for the things that our particular communities are perpetuating because we can’t expect [Black] activists to do all that work for us… so we need to be the ones that are pushing that change ourselves because we see it firsthand and we understand the problem with that.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.