By Eva Zhu —

On my 20th birthday, my friend gifted me a multi-coloured skateboard. That summer, I spent endless hours learning to ride it, and falling more times than I could count.

Four years later, I’m still skating and loving it more than ever—even though I’ve endured a torn ACL, a severely bruised hip and numerous scars.

It’s not easy being a woman who skates. The male-dominated sport has had a reputation for being unfriendly to girls and women. The legendary skaters frequently referenced when talking about the history of the sport are usually men: Tony Hawk, Rodney Mullen and Mark Gonzales, to list just a few.

While there has been a surge in female and nonbinary skaters in the past decade, and groups have surfaced to promote inclusivity in skateboard culture, local scenes often lack this representation.

In my city of Vancouver, there are three high-profile women skateboarders: Breana Geering, Fabiana Delfino and Una Farrar.

In a blog post for Urban Outfitters, Farrar says she started skating at age 12, and her progression was always with the boys.

“I didn’t skate with a girl until I was probably 17. Maybe last year even. And now it’s crazy because I have this whole community of girls to skate with. Growing up there were a couple older women at the park that would come through but I never had a session and my progression was always with the guys. Now that’s changed.”

But when I cruise around, I still don’t see very many female skaters on the streets or even at skate parks.

Representation in media

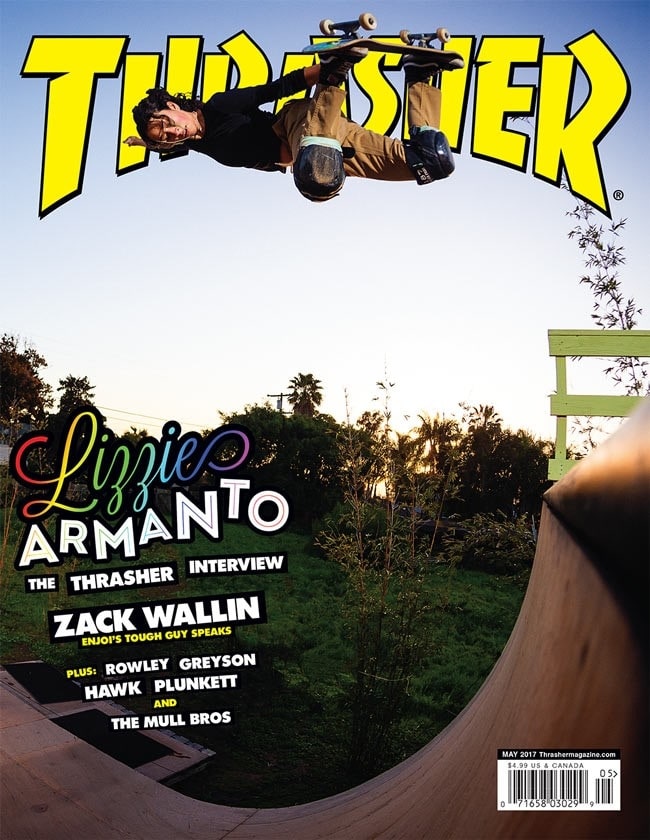

While big skateboarding magazines like Thrasher and Transworld Skateboarding have featured women in their pages, it’s rare. San Francisco-based Thrasher, wildly popular among skateboarders with a circulation of about 100,000, has only given one woman the cover since its inception in 1981.

For the August 2017 issue, the magazine published a women’s special issue, with Lizzie Armanto — one of the world’s best vert skaters — on the cover. But that’s it.

Kerria Gray, a photographer who wrote her master’s thesis on women and nonbinary skaters and their place in skateboarding, says magazines need to do more to champion women and queer skaters.

“There was always this undercurrent of sexism in a lot of the media. The fact is that magazines like Thrasher will have one women’s special and that’s it, instead of trying to make an effort to be inclusive, issue after issue,” says Gray.

Gray also points to big sport apparel brands not stepping up and sponsoring more women. Companies like Nike, Adidas, Converse and Vans sponsor far fewer women than men, she says.

“A large cultural shift isn’t really happening. I like that media is slowly becoming more inclusive, but I don’t want people to see that and think it’s happening across the board,” she says.

A quick look at Nike Skateboarding’s team shows this stark disparity between the genders. On their team of 54 skaters, only 7 are women and non-binary people. On Adidas’ team, only one person on their team of 27 is a woman (Nora Vasconcellos). Converse Cons also only sponsors one woman (Alexis Sablone) out of a 20 person team. Even Vans, arguably the most inclusive skateboarding brand, sponsors only 6 women in its 46 person team.

For this article, I reached out to Thrasher Magazine to request an interview, but didn’t receive a response in time for publication.

The local scene

Ciara Wilson, a 20-year-old Vancouver skateboarder, says she doesn’t like to go to skateparks because she is usually the only woman there.

“I skate alone a lot of the time and often don’t like to skate actually in the park for fear of judgement or people being mean so there have been times where I end up skating to the side or don’t even go to the park,” she says.

Wilson says she’s gone to skate parks where local male skaters would ignore her when she tries to introduce herself or strike up a conversation. She has even gotten eye rolls when accidentally getting in their way, which causes her to feel out of place, she says.

When guys at the skate park do talk to her, Wilson says she feels the need to evaluate if it’s coming from a place of friendship or romantic attraction.

I know what she means. When I skate in public, I often get glares from people and unwanted comments about being a woman skater from others.

In Ottawa last year, my friend and I went to a skate park so I could practice a basic trick, known as an “ollie,” but I felt so intimidated by a group of unfriendly teenage boys practicing tricks together that I became too self-conscious to even attempt an ollie.

To feel more comfortable, Wilson says she often goes to skate parks with male friends. “Those guys make me feel safe and like I’m actually a skater when we go skate, which is rad. However, it’s sad to think that I have to rely on having a guy with me sometimes to feel like I’m a part of the skate community,” she says.

Meanwhile Stephanie, a 21-year-old Toronto skateboarder who spent a year skating in Australia and didn’t want to give her last name, says she goes to the skate park early in the morning to avoid obnoxious teenagers and “holier-than-thou” skaters.

Instagram skate culture

While local skate scenes aren’t the most welcoming to female skaters, Instagram — a place skaters often go to post photos and videos — has become a whole other world of toxicity and sexism.

Women skateboarders are often criticized by men, not only for trying new tricks but for what they wear — especially when they dress in more “feminine” clothes.

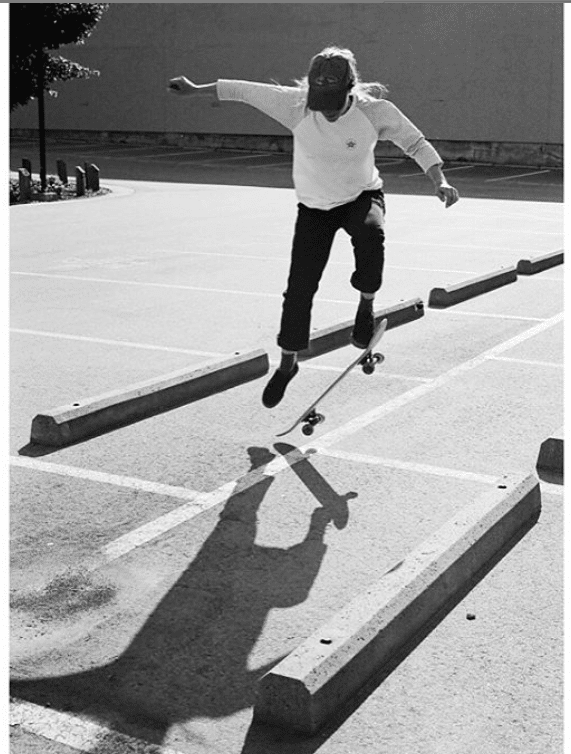

Take Farrar. She dresses in typical skater clothing, wearing baggy jeans and a boxy t-shirt, like many of her male counterparts. She’s unanimously cheered on by both women and men on the social media platform. Most of the more famous women in skateboarding dress similarly.

But when female skaters on Instagram dress in more shape conforming or fashionable clothing, they are often bullied by their male counterparts.

“There seems to be this assumption that women trying to skate are doing it for clout, are dressing and skating for men and are just generally inferior to men,” Wilson says.

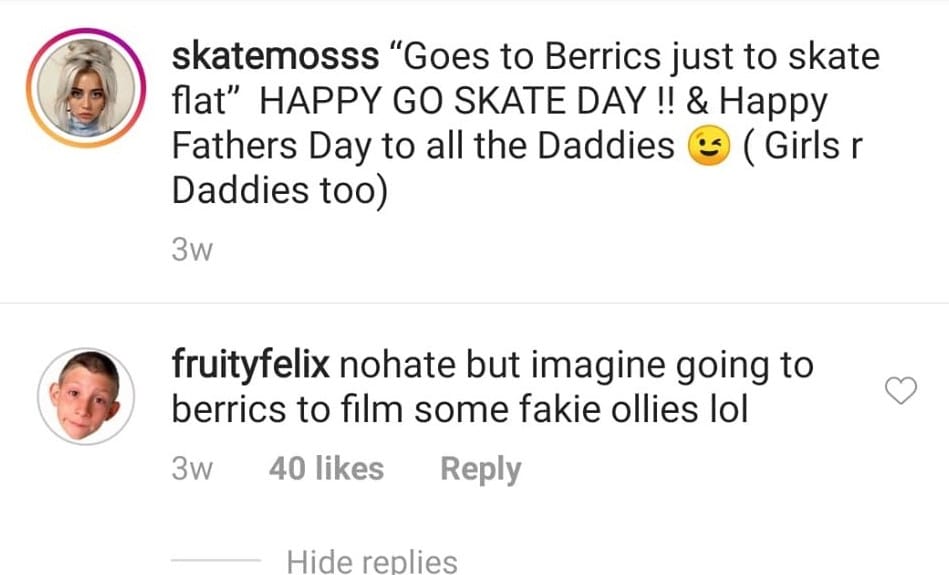

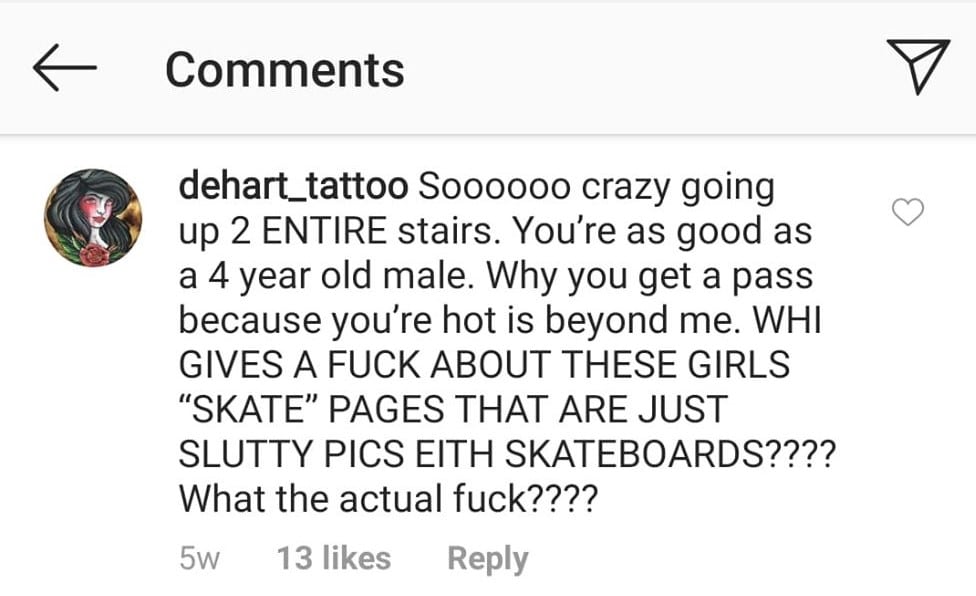

Victoria Taylor is another talented skater who can pull off an advanced trick of landing a 360 flip, after only three years in the sport. On Instagram, Taylor, who is from Los Angeles posts videos of her skating and photos of herself in trendy clothing.

Despite that, her feed is riddled with hateful comments from men.

“no hate but going to berrics to film some fakie ollies lol,” says one comment.

“Soooooo crazy going up 2 ENTIRE stairs. You’re as good as a 4 year old male. Why you get a pass because you’re hot is beyond me. WHO GIVES A F— ABOUT THESE GIRLS ‘SKATE’ PAGES THAT ARE JUST SLUTTY PICS WITH SKATEBOARDS????? What the actual f—????” says another.

Jennifer Charlene is a skater from Brooklyn who also gets numerous hate comments when she posts a skate video. Because she’s not as good as some women skaters, guys flock to her Instagram to leave jealous comments.

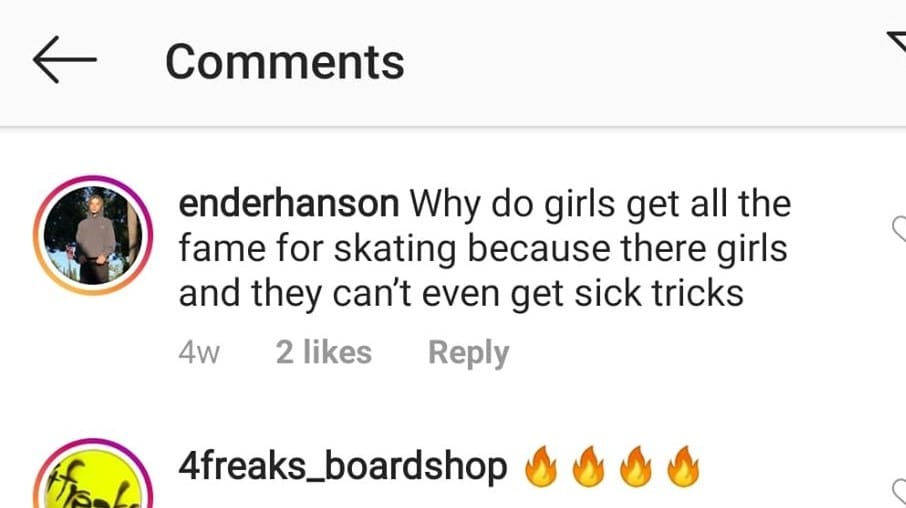

“Why do girls get all the fame for skating because they’re girls and they can’t even get sick tricks,” says a post on one of her videos.

Comments like these suggest Instagram may no longer be a platform for people to post videos of themselves having fun skateboarding. It’s become a place where people who aren’t as skilled at skating get bullied. How are women and girls in skateboarding supposed to showcase their progress and new tricks if they constantly get hate?

To Wilson, the toxic skate culture on Instagram is pushing women and girls away from trying out skateboarding.

“The jealousy, arrogance and blatant disrespect on Instagram towards women who skate just further proves the ‘man’s world’ that skateboarding continues to be and isolates, alienates and discourages women and girls from getting into the sport,” she says.

Inclusive skateboarding groups

To make the skateboarding community more inclusive to women and nonbinary folk, skaters have been forming inclusive groups and safe spaces for people of all skill levels.

In Vancouver, one of these groups is Vancouver Queer Skate (VQS). Jonah Bayley, a queer skater, started VQS at the beginning of 2019 when he realized there weren’t any queer friendly skateboarding groups in Vancouver.

“I didn’t know if anyone would even be interested but I decided to do it anyways. I got a bunch of stickers printed, made an Instagram account, put up posters all over Davie street and other queer-dense areas of Vancouver, and reached out to skaters that I found on Instagram,” he says.

Queer people are rarely represented in mainstream skate media, he says, and as a result they’re less likely to pick up a board and learn to skate.

To make skateboarding a much more women and queer inclusive sport, Bayley says skate brands and skate media need to stop supporting skaters who are “blatantly queerphobic and misogynistic because they’re good skaters.”

One of the biggest problems in skateboarding is that companies don’t encourage diversity in skateboarding, he says.

“If companies could put as much funding into encouraging diversity in skateboarding as they do into supporting every [cisgender heterosexual] white dude that’s on their team, the world of skateboarding would look very different than it does now.

Ultimately, for women, girls, and queer people to feel comfortable and confident skateboarding,

“It’s the responsibility of every skater in the skatepark to create a welcoming environment for anyone who is new to skateboarding. The amount of times that I have been too intimidated to skate in a park that’s full of rippers who don’t even say hello is crazy.

“An introduction goes a long way.”

As for Gray, she hopes that in 20 years, the culture around skateboarding will be more inclusive and be less male dominated.

“It just feels like our entire culture is having to shift in a lot of ways right now. There’s a lot of activism happening to shift these kinds of narratives. There’s obviously still so much work to do, but I think 20, 30 years from now, things will look really different. I feel hopeful about it.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.