By Vicky Qiao —

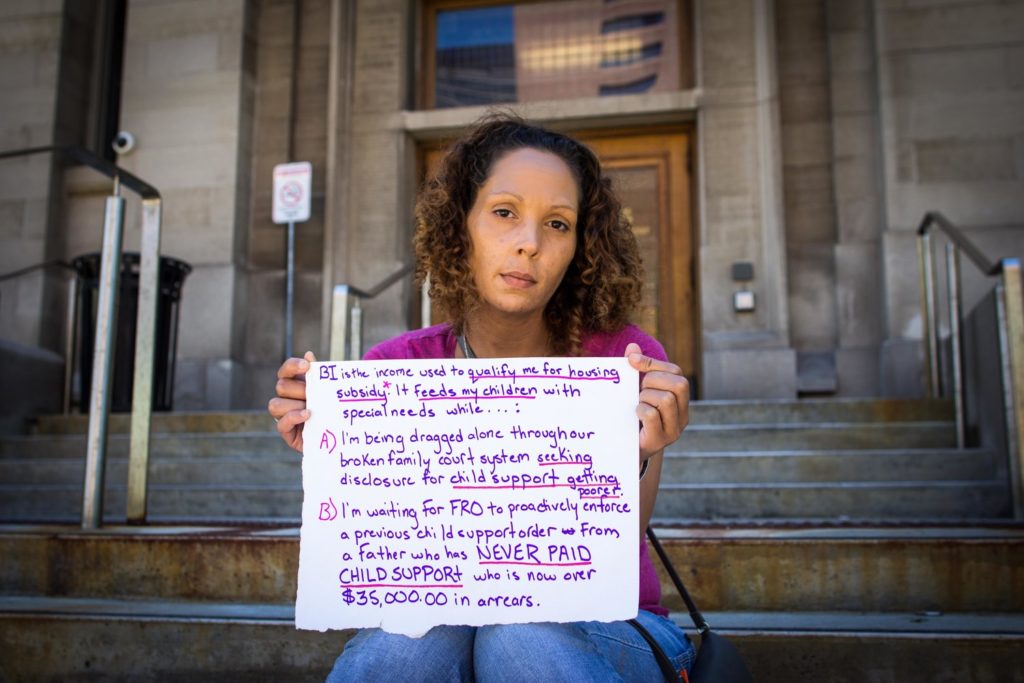

The woman in the photograph stares straight into the camera, her eyes calm yet exhausted. She is holding a sign with words written in purple marker. “I’m being dragged alone throughout broken family court system seeking disclosure for child support getting poorer.”

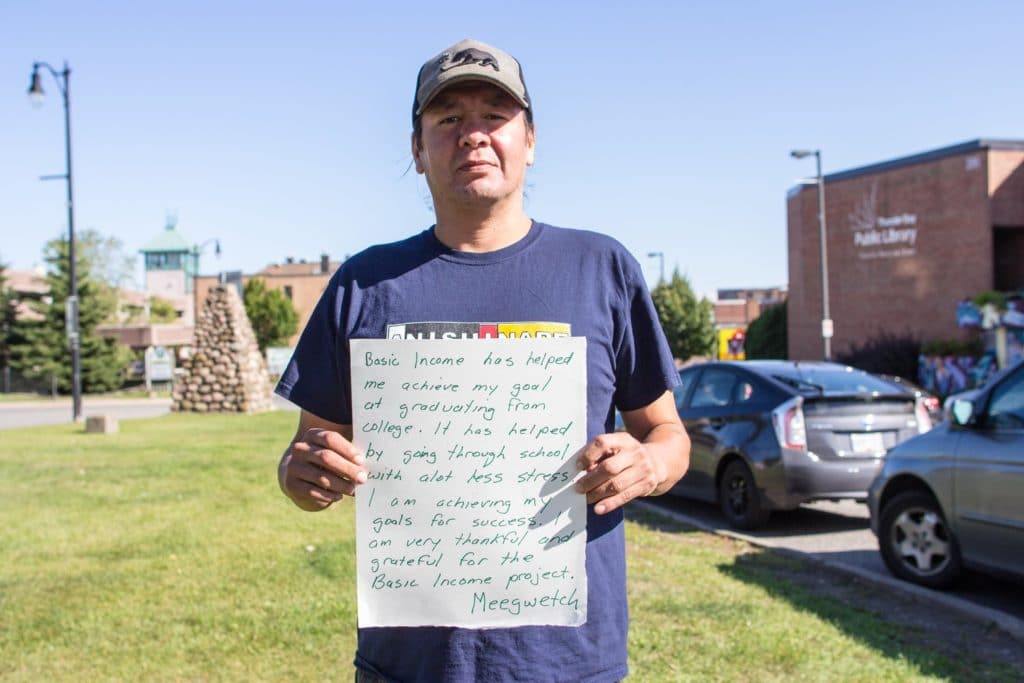

In another photograph, the man wears a blue t-shirt and is also holding a sign with a hand-written message: “Basic Income has helped me achieve my goal of going to college.” After a few more sentences, his hand-written message ends with the Anishinaabemowin for thank you, “Meegwetch.”

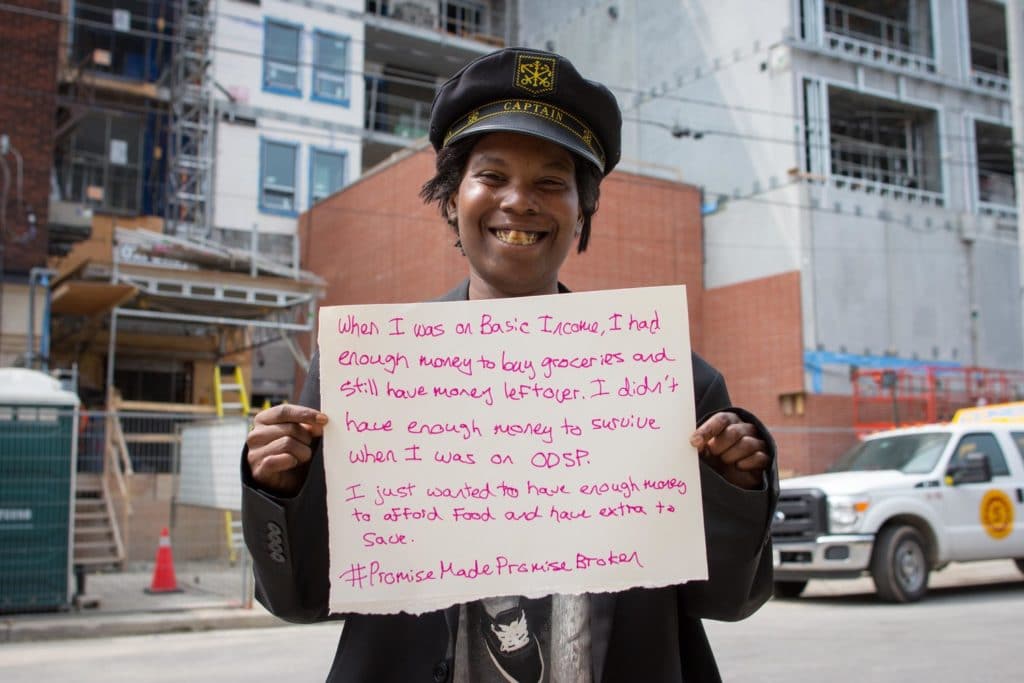

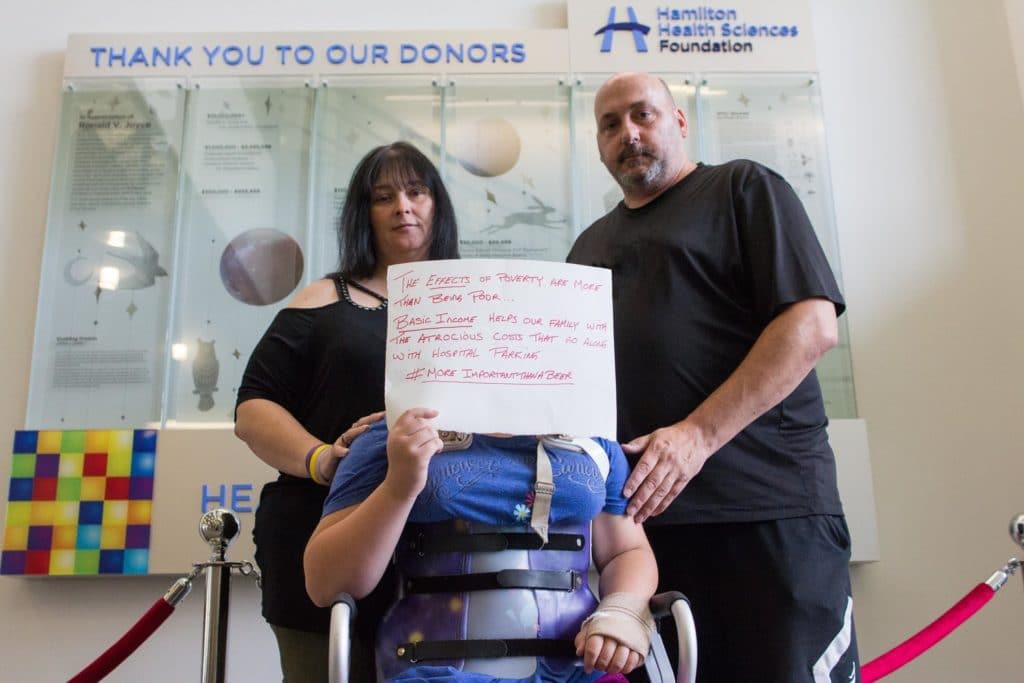

These are some pictures from the Humans of Basic Income portrait series, a project Hamilton photographer Jessie Golem started in 2018 to highlight the life-changing impact of basic income programs and put real people at the heart of what has become a complicated political issue.

Back then, she just wanted to tell the stories. Two years later, during this months-long pandemic that has cost thousands of Canadians their jobs, Golem’s series is gaining new traction.

“[Basic income] is a growing movement and right now, because of COVID, it’s more relevant than ever before,” she said in a recent interview.

The self-employed photographer, who is also the chair of the Hamilton Basic Income Group, has been speaking about basic income at webinars since the start of the pandemic, including a presentation to a working group of the Canadian Senate in early June.

Launched by Kathleen Wynne’s provincial government in February 2018, the Ontario Basic Income Pilot aimed to provide low-income people in Ontario with about $17,000 each per year for three years.

Golem was one of 4,000 recipients and used the income to help with the capital investment needed for her photography business. Things were starting to look promising, but six months into the project, the Doug Ford government scrapped it. She started her series then, to highlight how others were affected by the program and its demise.

If it had not been cancelled, she believes she would’ve been independent before the project was up.

“I would have been a full-time photographer and would not have needed to be on the basic income palette for the full three years,” she said. “Because with the way my business was growing and everything I ever predicted that I would have been making enough money two years into the pilot, that I would’ve not needed it.”

With the pandemic hitting the labour market, which spurred the federal government to provide assistance in the form of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) — up $2,000 per month for anyone who is out of work due to the virus or shut-downs related to the virus — the discussion around basic income has re-entered the public discourse.

“I think the CERB has highlighted the need for [the basic income program]. Because people actually know that you can easily lose your job, and what are you going to do? You need income,” said Tracy Smith-Carrier, an Associate Professor at King’s University College and a basic income advocate based in London, Ont.

“So instead of being in the position maybe a few months ago, where people were quick to blame other people for being in positions of unemployment. Now people are, I think, a little bit more understanding.”

A basic income program would help structure other support programs, such as Employment Insurance, which doesn’t benefit everyone and needs to be “significantly overhauled,” said Smith Carrier, adding that less than half of the unemployed population receive employment insurance.

“Everybody’s paying into this system who’s working, and only 40 per cent are actually able to, when they need that money, get employment insurance benefits,” said Smith-Carrier, who sits on the Basic Income Canada network advisory board.

CERB shows how basic income can help people

Some advocates have called for the federal government to make CERB a new “basic income” for people who are out of work. But Golem said the amount is not sufficient.

“There is just so much confusion and fear,” she said. “I’m on a number of Facebook discussion groups of people and so many people (are) like, I don’t know if I’m going to be able to get CERB now and I’m screwed if I don’t.”

Golem worries how workers in certain industries are going to return to the workforce after the pandemic, she said, as labour jobs are increasingly replaced by automation and technology.

“I think that we would have been more prepared and equipped if we had something like a basic income in place already and that we would alleviate so much fear and stress and anxiety.”

The concept of a basic income has long been a topic of debate in communities and countries around the world. While many anti-poverty groups and activists continue to campaign for basic income, some say such programs are not the solution.

“Our safety net is designed to address some needs that can’t easily be addressed by cash alone. Some parts of the safety net are designed to replace income, such as Employment Insurance, pensions and disability insurance programs,” wrote Noah Zon, the former policy director for Maytree, a Toronto-based anti-poverty foundation.

“In each of these areas, we have seen some significant gaps emerge, leaving some people poorly covered,” said Zon in the 2016 policy brief.

Instead of basic income, he said the government should enhance employment insurance policies and invest in the federal Working Income Tax Benefit, which is a refundable tax credit that is meant to increase incomes for low-income individuals who are working.

A fundamental policy shift

Gregory Mason, an economics professor at the University of Manitoba, agrees COVID-19 has demonstrated the need for a resilient social safety net, but said implementing one would require a fundamental policy shift.

Basic income should not be mandated by provinces, but should be a federal program like the Canada Child Benefit, he said. Then provincial governments could make arrangements to top up the funding based on individual provincial needs, said Mason, who has been researching and teaching public policy.

“I think most Canadians who are filing taxes, and who are paying taxes, would pretty well insist that the program has to have that kind of integrity, it has to have that kind of insight.”

Mason acknowledged concerns that a basic income program could spark part-time, low wage employees to withdraw from the labour market, but said the program should be flexible enough to allow for necessary adjustments that would let small businesses survive and employees have an adequate income.

“As we learn about its effects, we can make adjustments,” he said. “So rather than trying in a situation where many people want perfect programs to start with,I argue let’s start with a good enough program and then modify it as we need to.”

In the meantime, Golem will continue to help the Humans of Basic Income tell their stories. And by doing so, she’ll keep telling hers.

“I’ve shared my pictures and told the stories behind them and everything, and people find the whole thing to be very inspiring, it puts a human face to this issue,” she said. “It has been a really great way to reach out and educate people.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.